When Clearing got underway for another year, the Telegraph reported that rising tuition fees had caused a sharp increase in demand for ‘jobs-based’ degrees.

This kind of story is becoming more commonplace. Students taking up vocational degrees and job-related learning rather than studying more ‘traditional’ subjects.

The key passage comes at the end of the article:

“But Prof Alan Smithers, director of the Centre for Education and Employment Research at Buckingham University, said the shift in applications may be ‘short-sighted’.

“‘Fees are causing students to think a lot more seriously about the part that going to university is going to play in their future lives and whether they will get a good return for their investment,’ he said.

“‘But it is a little bit short-sighted to simply concentrate on a career above all else at the age of 18. Studying a subject you love, such as the humanities or English literature, will enhance your life and could throw up future employment opportunities that you’re not yet aware of.'”

If fees and the future are making such an impact, how much does subject matter in the long run? Students risk moving away from a subject they enjoy just because it doesn’t visibly link up with a certain career.

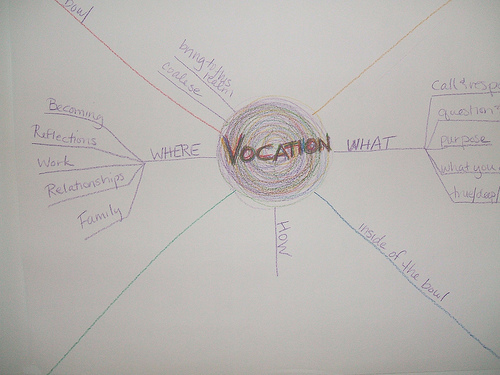

Interests and Passions

Research from YouthSight suggests that students still pick subjects based on their interests. However, I wonder how those interests are defined now. What compromise is made when choosing a subject?

The YouthSight data also suggests that business students are far less likely to be studying due to a love for the subject. This is a concern. Why would you choose to study something you weren’t that keen on learning about?

Perhaps it’s expected of you. Perhaps you like the salary prospects. Perhaps your friends are doing it.

These aren’t reasons for choosing a degree or a subsequent career. Same for following a passion. You need to put in work that you’re not so keen on to allow the passion to come to fruition. And passion is overrated anyway. The situation is far more compicated. Don’t take my word for it, check out Cal Newport’s extensive back catalogue of posts on the subject. Here’s a selection to get you started:

- Your Career Is Not a Disney Movie

- Zipcar CEO’s Dangerous Advice On Passion

- Why ‘follow your passion’ is bad advice (CNN)

Regardless of where you stand on passion, and whether or not you claim to have found yours, now could be the worst time to shy away from a course you want to do.

Fees force a rethink, but that doesn’t always mean you end up seeing things differently. Imagine having to put in some unenjoyable work for a subject you really like. Annoying, but usually manageable. Now imagine doing the unenjoyable work for a subject you were never that keen on in the first place. Double whammy. There’s no motivation to get you motivated.

And the reward in the distant future is still based on that vocational subject you’re already not that keen on. If that’s not being set up for a fall, I don’t know what is.

Do you make the choice or is the choice made for you?

A recent study of humanities graduates at Oxford between 1960 and 1989 found that degree subject was not a barrier to most careers. This study only covers Oxford (one university is hardly indicative of the entire HE sector) and doesn’t take into account almost a quarter of a century of growing student numbers since 1989. Nevertheless, the report provides a hint that what you study doesn’t need to be linked to a direct career path. Choosing History doesn’t penalise you from a wide range of jobs, for instance.

Does a more ‘traditional’ course hold less weight than it used to? Are we stuck with making a choice between a degree that will get you a job and a degree that will get you enthused?

I doubt it. Learning and discovery comes more naturally when you appreciate your course. You have room to find out what makes you tick. Studying won’t feel so forced.

In other words, you gear yourself up for a fall when you’re only on a course for what takes place after you graduate.

Your attitude matters. Although it sounds wrong, the course is more important than the grade. It sounds wrong because we generally focus on what an employer wants to see. In reality, you need to focus more on yourself. Who is this mythical employer in your mind?

Study a subject you respect and enjoy. I know that’s far too simplistic, but so is slogging through a course in the hope that it’ll be worth it for the massive wodge of cash or better prospects at the end. It’s a false trail, because you’re concentrating more on the content than your own ability.

So when I say the course is more important than the grade, it’s based on your choice and focus on developing your abilities. From my perspective, that’s all the more reason to choose a degree that you want to spend three or more years of your life poring over.

In my next post, I’ll look at ways you can focus on your career no matter what you’re studying.