Essays. They’re all about the numbers, right? Get that wordcount and you’re free.

What would you do to get rid of an all-nighter, just before the assignment is due in?

Perhaps I can interest you in a few other methods…

Even paced

Deadlines are all different. You may have a week, a fortnight, a month, even the entire term before a piece of work is due in. Let’s say you have a couple of weeks from start to finish for a 2,000 word essay. You would need to write fewer than 150 words a day in order to get to the 2k mark.

Okay, you’ll need to leave time to edit and add more when you need to delete some of the less convincing stuff, but you only need to up your game to 200 words a day and you’ll have several days left to play with.

Quick first draft

This method isn’t given anything like the amount of love it should. When you’re set an assignment, it’s worth writing down what you can from the outset. You may get stuck at 100 words or you may cruise toward the limit. Whatever happens, you’ve started. Work from that place and it’s suddenly less daunting.

Outline in advance

It’s easy to lose track of all your amazing ideas. Start with a plan of what you want to say and the important points you need to get down in your essay.

Your plan can change later. The main reason for the outline is to give you a clear structure to work with. You won’t be left flapping about at the last minute, desperate to remember all the thoughts you had buzzing around your head when you were first given the assignment.

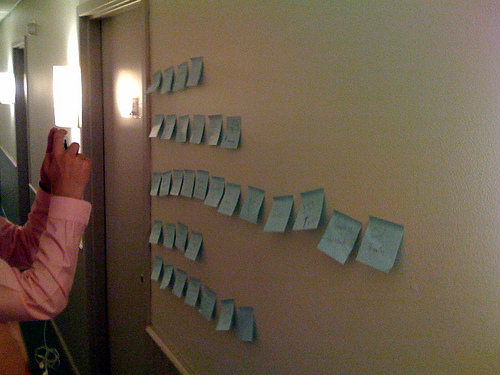

When it seems clear in your head, get those ideas down on paper so you don’t forget later.

Dictate

Gone are the days when you needed a dedicated dictaphone for a quick voice note. Now your phone will record stuff admirably (unless you’re producing broadcast stuff, of course).

Do you express yourself better when spoken out loud? Then start recording your voice! Speak your essay’s first draft and jot it down later. Even better, dictate it to a voice recognition tool that can print the text up on screen for you.

Whatever you can manage, chatter away about the topic and get that essay going now.

Quote first

I’ve never been a big fan of this one, but it might help you. When you’re stuck for ideas, grab some books on the subject you’re writing about and find some juicy quotations to work around. Let the work of others inspire you.

I’m not that keen on this approach because it may set you down a false trail or lead you to take on someone else’s ideas, rather than allowing you to form your own conclusions. There are dangers associated with this method.

Nevertheless, finding some great leads to use in an essay can be a step closer than simply doing some research before you get started. The very fact that you have some choice quotes typed up can form as a way to get words on the screen, stopping the scary blank white page. You may also stumble upon a theme or outline emerging from what you’ve found.

—

How do you get started on essays? Which approaches work for you?