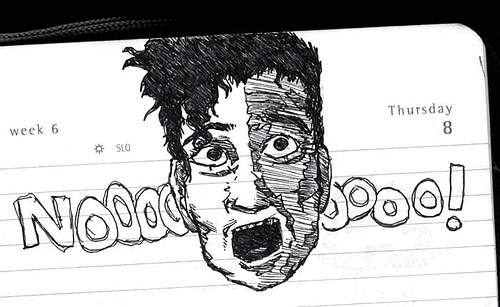

Alan Cann calls this one ‘a bit depressing‘.

A new study found that:

“…a replacement of manually generated feedback with automatically generated feedback improves students’ perception of the constructiveness of the provided feedback substantially (undergraduate) or significantly (postgraduate).”

I don’t know why more respondents preferred automated feedback. Could it be because students aren’t frequently told that feedback is best used in order to improve on future assignments?

How clearly are students made aware of the need for ongoing assessment? If you don’t fully appreciate the way detailed and specific feedback can help you, the auto-generated feedback may seem a great idea. Get the grade and some general advice and walk away with all the info you think you need.

On the face of it, an automatic report makes sense. Anything beyond that seems like a time commitment with little gain. There may seem no point poring over the details when the essay has already been submitted.

But feedback isn’t for the past, it’s for your future work. General advice and rough guidelines won’t do more than weakly nudge you in the right direction. For the best hope of improvement, you need to respond to detailed information that is tailored to your specific circumstances.

Detailed feedback may be hard to swallow when you have a lot to improve. That may also explain why some people would prefer automatically generated reports. They feel one step removed, so you almost have an excuse not to listen. It wasn’t aimed exclusively at you, so there’s wriggle room and you don’t need to take the advice so seriously.

Whatever flavour your feedback comes in, consider these points:

- Have an open mind – You may not like to hear that you’re not perfect, but the more you put your head in the sand, the less likely you are to even get close to perfection. Make the opportunity to action problem areas rather than defend yourself.

- Think of the future – Work out what you would have done to improve the essay and remember that so you can make a similar effort in your next piece of coursework.

- Ask more questions – When you’re not sure what the feedback means, speak to your tutor for more information. The key is to get a detailed understanding of how you can improve, so keep searching until you have a plan on which steps to take.

Automatic feedback isn’t useless, but it needs context and it should never be the only type of feedback given. It’s not enough when the aim of higher education is to dig deep and explore the possibilities.

There are loads of things you can do with your assignments when you get them back. The grade is just one part of it. Check out these links from the TUB archives for more tips on using your essay feedback: